Licensing Overhaul - The Whiteboard Strikes Back

In case you missed it, you can see Part 1 of the series here: Part 1 - A New Challenge Last week, I introduced my second biggest work project to date. Shortly after re-vamping the License structure, my PM decided he also wanted to change what some of the licenses allowed the user to do. Upon digging into the code, I discovered a tangled web of multiple checks and confusion. I thought there was no way I could finish in 10 weeks. Thankfully my estimates were in correct, and some solid design work saved the day! Today, I will discuss the design aspects of my new implementation. Starting out, I knew this project would be not only big and rather difficult but that it would also be a catastrophe later if I did not do it well. Even so I was surprised by just how ornery the project got before the end. To be certain, I knew at the outset that I wanted my design to be better and if possible to be more Object-Oriented that the previous implementations had been. However I had very little idea what that meant at the time. As I progressed through the project some goals did eventually become apparent. I am listing them here, in the hopes that I might learn to generate these design goals earlier in the project going forward.

In case you missed it, you can see Part 1 of the series here: Part 1 - A New Challenge Last week, I introduced my second biggest work project to date. Shortly after re-vamping the License structure, my PM decided he also wanted to change what some of the licenses allowed the user to do. Upon digging into the code, I discovered a tangled web of multiple checks and confusion. I thought there was no way I could finish in 10 weeks. Thankfully my estimates were in correct, and some solid design work saved the day! Today, I will discuss the design aspects of my new implementation. Starting out, I knew this project would be not only big and rather difficult but that it would also be a catastrophe later if I did not do it well. Even so I was surprised by just how ornery the project got before the end. To be certain, I knew at the outset that I wanted my design to be better and if possible to be more Object-Oriented that the previous implementations had been. However I had very little idea what that meant at the time. As I progressed through the project some goals did eventually become apparent. I am listing them here, in the hopes that I might learn to generate these design goals earlier in the project going forward.

- I wanted my design to provide an explanatory interface to the user. I wanted it to be clear from looking at a simple call what permission was desired.

- I wanted permissions presented to be general enough that only a few would be needed, and that these would be clear in their intent.

- I wanted to ensure that any code written in this phase was stable enough that it wouldn’t change should any new scope be added. To be more specific, if the covered permissions or the data types that were covered ever increased I wanted the present code to remain unchanged, both in syntax and in outcome.

- I wanted my code to be segregated enough that if ever the original License Manager need be replaced, it would be done with a minimal effort to update the new code base, and without disturbing the Permission request calls listed above.

- Lastly, I wanted my new code to be easy for anyone who came after to learn and to use, so as to reduce the multiple versions of the same License check that were seen in previous implementations.

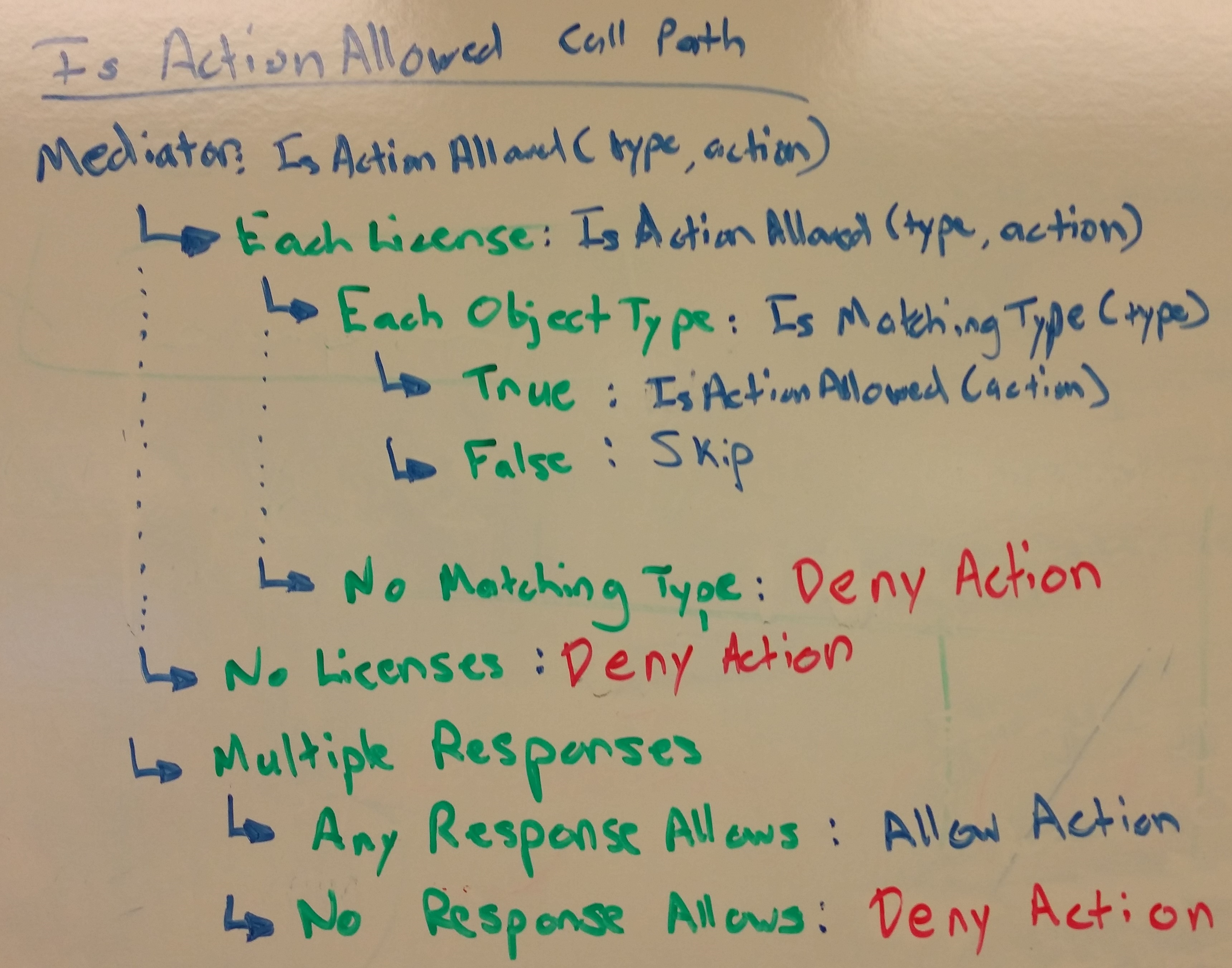

Again, I admit that these goals were not all so verbose when I started the project, but I did set out with something very like this in mind as I began to design my solution. During the first few weeks of the project, I spend a great deal of time sifting through the code, concentrating on the Main UI area, and on the areas which my PM had mentioned he wanted to change. I made note of the patterns, and anti-patterns that I found throughout, and used these to inform my design choices. While sorting through all of that information, I also spend a lot of time at a whiteboard drafting, and redrafting the objects and responsibilities that I wanted to manage, in order to solve the problem.Overall a great deal of attention as spend on their interfaces. The picture below shows the resulting system that I developed, as drawn on a whiteboard.  The workhorse of my solution was the Mediator, which was responsible for routing the Permission Request from any end point through the licenses that the system currently had checked out, and provide a Boolean response to either allow the request or to deny it. To facilitate its work, it is injected with the License Manager, which is used to determine what Licenses, if any, are presently checked out for the system, and then it called on the Factory. The Factory, per its namesake, would create License Objects prepared to answer the Request queries being routed to them by the Mediator. All of this architecture was created to support the abstraction of the idea of a Permission, that is an allowed action on a particular data type. A License in this sense, is composed by the series of Data types and their allowed actions under that License. The Connection between Data Type and Action Type are represented by the Object Type object. Now, some of the more seasoned developers reading this will probably be shaking their head at this name, but I assure you there was a good reason for it. In the first place, the code base I had to work with had another meaning for the term ‘data type’ and as a result the only other suitable term that myself, and an English major could conjure up that meant something similar to our intention was ‘object’. Getting back on topic, there are several classes where a 1 to N relationship is specified. In laymen’s terms, this means that it is possible for multiple of the ‘N’ type objects to housed under the ‘1’ type object. This is a oversimplification, it will suffice for the moment. The reason there are several 1 to N relationships is because I wanted to abstract the responsibility for know whether or not a particular action was allowed, while simultaneously providing a simple and easy to use interface for such a query. What I ended up creating is best show by the “call-stack-like” write up shown in the picture below:

The workhorse of my solution was the Mediator, which was responsible for routing the Permission Request from any end point through the licenses that the system currently had checked out, and provide a Boolean response to either allow the request or to deny it. To facilitate its work, it is injected with the License Manager, which is used to determine what Licenses, if any, are presently checked out for the system, and then it called on the Factory. The Factory, per its namesake, would create License Objects prepared to answer the Request queries being routed to them by the Mediator. All of this architecture was created to support the abstraction of the idea of a Permission, that is an allowed action on a particular data type. A License in this sense, is composed by the series of Data types and their allowed actions under that License. The Connection between Data Type and Action Type are represented by the Object Type object. Now, some of the more seasoned developers reading this will probably be shaking their head at this name, but I assure you there was a good reason for it. In the first place, the code base I had to work with had another meaning for the term ‘data type’ and as a result the only other suitable term that myself, and an English major could conjure up that meant something similar to our intention was ‘object’. Getting back on topic, there are several classes where a 1 to N relationship is specified. In laymen’s terms, this means that it is possible for multiple of the ‘N’ type objects to housed under the ‘1’ type object. This is a oversimplification, it will suffice for the moment. The reason there are several 1 to N relationships is because I wanted to abstract the responsibility for know whether or not a particular action was allowed, while simultaneously providing a simple and easy to use interface for such a query. What I ended up creating is best show by the “call-stack-like” write up shown in the picture below:  As I mentioned earlier, the Mediator would route the query to the Licenses which were checked out at the time. So each license is asked whether or not it supports the requested action. To determine this, each License will in turn find the matching Object type of the query, if it has one, and will further route the request. The ObjectType then response based on whether or not it has permission for that action. Since the number of licenses is unknown, some additional check are needed. For example, it makes sense to just skip the checks if no licenses are checked out, since there would be no response. However if multiple licenses are present, then some rationalizing needs to be done on their multiple responses. Thankfully, the PM decided that it was sufficient to allow the action if at least one of the Licenses that was checked out allowed it. That is really all the more complex it got. After the appropriate associations were made to the various license. This basically concludes the design portions, and data types, it was a simple matter of tracking down what code I needed to change and how. Admittedly, that process took nearly a month, and would have been a disaster had it not been for some stellar QA help. But overall, I was able to finish the vast majority of the code in about 6 weeks, and the QAs were able to catch up and feel secure in their approval around 8 weeks. Naturally being nearly a month ahead of schedule made the PM very happy! So this week we covered the goals of my new design, the general responsibility of the software objects that I used to create the new system, as well as the Request routing hierarchy. Come back next week, when I’ll be discussing the concrete benefits of the new design, as well as some of the draw backs. Thanks as always for your time! Part 3 - Return of the Designer

As I mentioned earlier, the Mediator would route the query to the Licenses which were checked out at the time. So each license is asked whether or not it supports the requested action. To determine this, each License will in turn find the matching Object type of the query, if it has one, and will further route the request. The ObjectType then response based on whether or not it has permission for that action. Since the number of licenses is unknown, some additional check are needed. For example, it makes sense to just skip the checks if no licenses are checked out, since there would be no response. However if multiple licenses are present, then some rationalizing needs to be done on their multiple responses. Thankfully, the PM decided that it was sufficient to allow the action if at least one of the Licenses that was checked out allowed it. That is really all the more complex it got. After the appropriate associations were made to the various license. This basically concludes the design portions, and data types, it was a simple matter of tracking down what code I needed to change and how. Admittedly, that process took nearly a month, and would have been a disaster had it not been for some stellar QA help. But overall, I was able to finish the vast majority of the code in about 6 weeks, and the QAs were able to catch up and feel secure in their approval around 8 weeks. Naturally being nearly a month ahead of schedule made the PM very happy! So this week we covered the goals of my new design, the general responsibility of the software objects that I used to create the new system, as well as the Request routing hierarchy. Come back next week, when I’ll be discussing the concrete benefits of the new design, as well as some of the draw backs. Thanks as always for your time! Part 3 - Return of the Designer